THE JEMEZ MOUNTAINS OBSIDIAN SOURCES

Distributed in archaeological contexts over as great a distance as Government Mountain in the San Francisco Volcanic Field in northern Arizona, the Neogene and Quaternary sources in the Jemez Mountains, most associated with the collapse of the Valles Caldera, are distributed at least as far south as Chihuahua through secondary deposition in the Rio Grande, and east to the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles through exchange. And like the sources in northern Arizona, the nodule sizes are up to 10-20 cm in diameter; El Rechuelos, Cerro Toledo Rhyolite, and Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio) glass sources are as good a media for tool production as anywhere. While there has been an effort to collect and record primary source obsidian, most effort has been expended to understand the secondary distribution of the Jemez Mountains sources. Until the recent land exchange of the Baca Ranch properties, the Valles Rhyolite primary dome (Cerro del Medio) was off-limits to most research. The discussion of this source group here is based on collections by Dan Wolfman and others, facilitated by Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the Museum of New Mexico, and collections courtesy of the Valles Caldera National Preserve and Anna Steffen (see Broxton et al. 1995; Shackley 2005; Wolfman 1994).

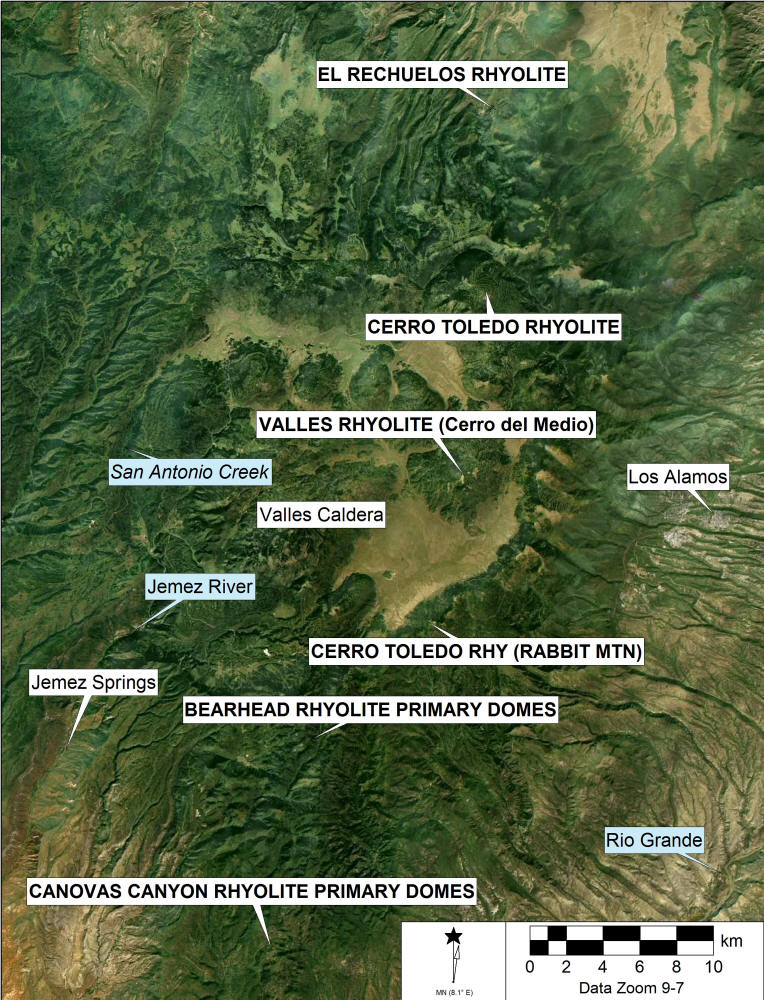

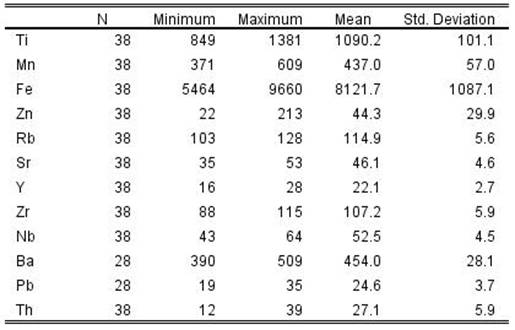

Due to its proximity and relationship to the Rio Grande Rift System, potential uranium ore, geothermal possibilities, an active magma chamber, and a number of other geological issues, the Jemez Mountains and the Toledo and Valles Calderas particularly have been the subject of intensive structural and petrological study particularly since the 1970s (Bailey et al. 1969; Gardner et al. 1986, 2007; Heiken et al. 1986; Self et al. 1986; Shackley et al. 2016; Smith et al. 1970; Figure below). Half of the 1986 Journal of Geophysical Research, volume 91, was devoted to the then current research on the Jemez Mountains. More accessible for archaeologists, the geology of which is mainly derived from the above, is Baugh and Nelson’s (1987) article on the relationship between northern New Mexico archaeological obsidian sources and procurement on the southern Plains, and Glascock et al’s (1999) more intensive analysis of these sources including the No Agua Peak source in the Mount San Antonio field on the Taos Plateau at the Colorado/New Mexico border (see also Shackley 2005).

Aerial rendering of a portion of the Jemez Mountains, Valles Caldera, sources of archaeological obsidian and relevant features

Analysis of major and minor compounds for Jemez Mountains and Taos Plateau obsidian sources (Bearhead and Canovas Canyon rhyolite obsidian below)1

|

Sample |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

CaO |

Fe2O3 |

K2O |

MgO |

MnO |

Na2O |

TiO2 |

|

Cerro Toledo Rhy . |

|||||||||

|

081199-1-7 |

78.31 |

11.3 |

0.19 |

1.13 |

4.13 |

0 |

0.06 |

4.27 |

0.09 |

|

Valles Rhyolite |

|||||||||

|

CDM3-B |

77.39 |

11.58 |

0.43 |

1.21 |

4.63 |

0.2 |

0.05 |

4.1 |

0.12 |

|

El Rechuelos |

|||||||||

|

080999-2-1 |

78.43 |

11.77 |

0.36 |

0.57 |

4.28 |

0 |

0.06 |

3.98 |

0.1 |

|

No Agua West |

|||||||||

|

081000-1-3 |

77.8 |

12.33 |

0.4 |

0.57 |

4.24 |

0 |

0.15 |

4.37 |

0.07 |

1

Samples analyzed by WXRF as polished nodules. All measurements in weight percent.Collection Localities

The collection localities discussed here are the result of a systematic survey to collect and record all the potential sources in the Jemez Mountains, as well as an attempt to understand the secondary depositional regime of the sources flowing out from the Jemez Mountains into the surrounding stream systems, as noted above.

El Rechuelos is mistakenly called "Polvadera Peak" obsidian in the archaeological vernacular (see also Glascock et al. 1999). Polvadera Peak, a dacite dome, did not produce artifact quality obsidian. The obsidian artifacts that appear in the regional archaeological record are from El Rechuelos Rhyolite as properly noted by Baugh and Nelson (1987). Indeed, El Rechuelos obsidian is derived from a number of small domes north of Polvadera Peak as noted by Baugh and Nelson (1987) and Wolfman (1994; see image here). Collections here were made at two to three small coalesced domes near the head of Cañada de los Ojitos and as secondary deposits in Cañada de los Ojitos (collection locality 080999-1&2). The center of the domes is located at UTM 13S 0371131/3993999 north of Polavadera Peak on the Polvadera Peak quadrangle. The three domes are approximately 50 meters in diameter each and exhibit an ashy lava with rhyolite and aphyric obsidian nodules up to 15 cm in diameter, but dominated by nodules between 1 cm and 5 cm. Core fragments and primary and secondary flakes are common in the area.

Polvadera Peak in background with glass producing rhyolite domes on the left and small domes in foreground.

Small nodules under 10-15 mm are common in the alluvium throughout the area near Polvadera Peak. It is impossible to determine the precise origin of these nodules. Presumably they are remnants of various eruptive events associated with El Rechuelos Rhyolite. The samples analyzed, the results of which are presented in the table below are compositionally similar to the data presented in Baugh and Nelson (1987) and Glascock et al. (1999).

El Rechuelos obsidian is generally very prominent in northern New Mexico archaeological collections. Although it is not distributed geologically over a large area, it is one of the finest raw materials for tool production in the Jemez Mountains. Its high quality as a toolstone probably explains its desirability in prehistory. Cerro Toledo Rhyolite and Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio), while present in large nodule sizes, often have devitrified spherulites in the glass, so more careful selection had to be made in prehistory. In nearly 500 nodules collected from the El Rechuelos area, few of the nodules exhibited spherulites or phenocrysts in the fabric. Additionally, El Rechuelos glass is megascopically distinctive from the other two major sources in the Jemez Mountains. It is uniformly granular in character, apparently from ash in the matrix. Cerro Toledo and Valles Rhyolite glass is generally not granular and more vitreous.

POLVADERA GROUP

El Rechuelos Rhyolite

Elemental concentrations for El Rechuelos Rhyolite obsidian source samples (all measurements in parts per million. Those samples with a "PP" prefix are from the Wolfman collection, those with the "08099" prefix are Shackley collection.

| SAMPLE | Ti | Mn | Fe | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba | Pb | Th |

| PP-1 | 451 | 6538 | 160 | 9 | 21 | 76 | 48 | 51 | ||||

| PP-2 | 434 | 7055 | 165 | 10 | 22 | 79 | 52 | 51 | ||||

| PP-3 | 430 | 6362 | 157 | 9 | 23 | 76 | 48 | 50 | ||||

| PP-1B | 436 | 6504 | 149 | 4 | 25 | 68 | 49 | |||||

| PP-2B | 420 | 6922 | 156 | 2 | 23 | 75 | 45 | |||||

| 080999-1-1 | 147 | 10 | 23 | 78 | 45 | 16 | ||||||

| 080999-1-2 | 150 | 10 | 23 | 79 | 46 | 20 | ||||||

| 080999-1-3 | 146 | 10 | 23 | 77 | 45 | 15 | ||||||

| 080999-1-4 | 147 | 10 | 23 | 78 | 45 | 11 | ||||||

| 080999-1-5 | 146 | 10 | 22 | 77 | 45 | 17 | ||||||

| 080999-1-6 | 148 | 10 | 23 | 78 | 46 | 10 | ||||||

| 080999-2-1 | 151 | 11 | 23 | 79 | 46 | 16 | ||||||

| 080999-2-2 | 157 | 11 | 24 | 80 | 48 | 20 | ||||||

| 080999-2-3 | 154 | 11 | 24 | 81 | 47 | 21 | ||||||

| 080999-2-4 | 148 | 11 | 24 | 78 | 46 | 17 | ||||||

| 080999-2-5 | 890 | 419 | 7658 | 36 | 155 | 10 | 21 | 76 | 48 | 0 | 22 | 35 |

| -6 | 851 | 452 | 7943 | 41 | 157 | 13 | 26 | 80 | 43 | 0 | 25 | 23 |

| -7 | 870 | 412 | 7624 | 40 | 149 | 16 | 25 | 78 | 53 | 0 | 20 | 19 |

| -8 | 848 | 412 | 7646 | 45 | 153 | 11 | 24 | 74 | 49 | 0 | 31 | 30 |

| -9 | 831 | 402 | 7672 | 37 | 151 | 16 | 22 | 77 | 42 | 1 | 29 | 27 |

| -10 | 876 | 416 | 7744 | 36 | 152 | 13 | 25 | 79 | 44 | 0 | 23 | 24 |

| -11 | 849 | 370 | 7456 | 43 | 144 | 13 | 20 | 69 | 48 | 0 | 23 | 28 |

| -12 | 903 | 427 | 7798 | 43 | 153 | 14 | 25 | 72 | 48 | 0 | 22 | 14 |

| -13 | 885 | 376 | 7607 | 41 | 147 | 12 | 21 | 72 | 45 | 0 | 26 | 21 |

| -14 | 1102 | 421 | 8445 | 37 | 149 | 12 | 27 | 72 | 49 | 0 | 26 | 15 |

| -15 | 829 | 409 | 7880 | 42 | 163 | 14 | 25 | 77 | 48 | 0 | 27 | 21 |

| -17 | 1057 | 396 | 8525 | 42 | 157 | 14 | 25 | 78 | 50 | 0 | 33 | 28 |

| -18 | 900 | 397 | 7841 | 43 | 152 | 12 | 28 | 76 | 47 | 0 | 26 | 26 |

| -19 | 1040 | 349 | 8094 | 38 | 137 | 9 | 24 | 74 | 49 | 0 | 21 | 19 |

| -21 | 988 | 412 | 8530 | 47 | 152 | 13 | 25 | 73 | 47 | 0 | 23 | 21 |

| -22 | 891 | 413 | 7969 | 40 | 157 | 13 | 20 | 77 | 46 | 0 | 25 | 22 |

| -23 | 871 | 381 | 7621 | 49 | 182 | 13 | 22 | 70 | 37 | 3 | 23 | 12 |

| -24 | 896 | 404 | 7680 | 42 | 153 | 14 | 21 | 74 | 47 | 0 | 23 | 20 |

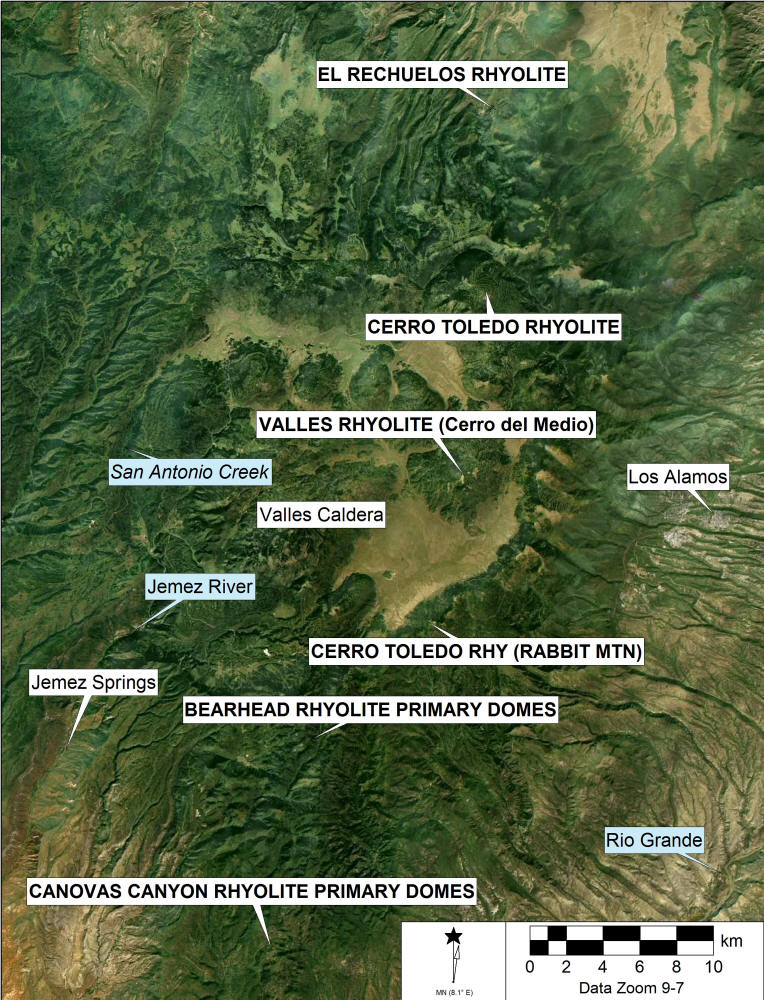

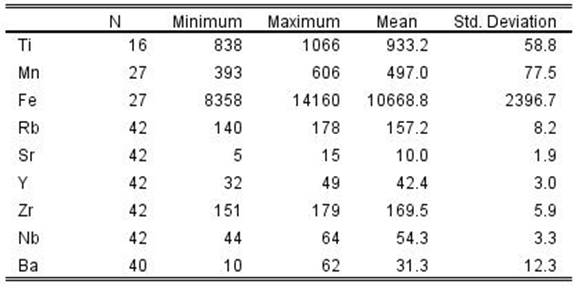

Mean and central tendency for El Rechuelos Rhyolite obsidian from data in table above

Rabbit Mountain Ash Flow Tuffs and Cerro Toledo Rhyolite

Known in the archaeological vernacular as "Obsidian Ridge" obsidian, is derived from the Cerro Toledo Rhyolite eruptions, and following Baugh and Nelson (1987) and the geological literature are all classified as Cerro Toledo Rhyolite (Bailey et al. 1969; Gardner et al. 1986; Heiken et al. 1986; Self et al. 1986; Smith et al. 1970).

There were six pyroclastic eruptive events associated with the Cerro Toledo Rhyolite:

All tuff sequences from Toledo intracaldera activity are separated by epiclastic sedimentary rocks that represent periods of erosion and deposition in channels. All consist of rhyolitic tephra and most contain Plinian pumice falls and thin beds of very fine grained ash of phreatomagmatic origin. Most Toledo deposits are thickest in paleocanyons cut into lower Bandelier Tuff and older rocks [as with the Rabbit Mountain ash flow]. Some of the phreatomagmatic tephra flowed down canyons from the caldera as base surges (Heiken et al. 1986:1802).

Two major ash flows are relevant here. One derived from the Toledo embayment on the northeast side of the caldera is a 20 km wide band that trends to the northeast and is now highly eroded and interbedded in places with the earlier Puye Formation from around Guaje Mountain north to Santa Fe Forest Road 144. This area has eroded rapidly and obsidian from this tuff is now an integral part of the Rio Grande alluvium north of Santa Fe. The other major ash flow is derived from the Rabbit Mountain eruption and is comprised of a southeast trending 4 km wide and 7 km long "tuff blanket" interbedded with a rhyolite breccia three to six meters thick that contains abundant obsidian erupted as lapilli during the Rabbit Mountain ash flow (Heiken et al. 1986). All of this is still eroding into the southeast trending canyons toward the Rio Grande. The surge deposits immediately south of Rabbit Mountain contain abundant obsidian chemically identical to the samples from the ridges farther south and in the Rio Grande alluvium, as well as in sediments above the Puye Formation between Española and the Toledo Embayment (Shackley 2005, 2012). Heiken et al. NAA analysis of Rabbit Mountain lavas is very similar to those from this study (1986:1810; see data here).

Lower Cochiti Canyon from Forest Road 289 looking south. Bandelier Tuff exposed on east canyon walls with Rabbit Mountain tuffs above eroding into Rio Grande. Sandia Mountains in background.

While Obsidian Ridge has received all the "press" as the source of obsidian from Cerro Toledo Rhyolite on the southern edge of the caldera, the density of nodules and nodule sizes on ridges to the west is greater by a factor of two or more. All these ridges, of course, are remnants of the Rabbit Mountain ash flow and base surge, and the depth of canyons like Cochiti Canyon is a result of the loosely compacted tephra that comprises this plateau. At Locality 081199-1 (UTM 13S 0371337/3962354), nodules on the ridge top are up to 200 per m2 with over half that number of cores and flakes. This density of nodules and artifacts forms a discontinuous distribution all the way to Rabbit Mountain. The discontinuity is probably due to cooling dynamics and/or subsequent colluviation. Where high density obsidian is exposed, prehistoric production and procurement is evident. At the base of Rabbit Mountain the density is about 1/8 that of Locality 081199-1, and south of this locality the density falls off rapidly. At Locality 081199-1 nodules range from pea gravel to 16 cm in diameter (Figures 3.14 and 3.15). Flake sizes suggest that 10 cm size nodules were typical in prehistory. Nodule sizes at Rabbit Mountain are up to 30 cm or more (Gauthier, personal communication, 2006).

Locality 081199-1 south of Rabbit Mountain in the ash flow tuff. This locality has the highest density of artifact quality glass of the Rabbit Mountain ash flow area. The apparent black soil is actually all geological and archaeological glass; one of the highest densities of geological and archaeological obsidian in the Southwest.

Mix of high density geological obsidian and artifact cores and debitage (test knapping) at Locality 081199-1 south of Rabbit Mountain. Nodules » 200/m2, cores and debitage » 100/m2, some of the latter could be modern.

Cerro Toledo Rhyolite obsidian both from the northern domes and Rabbit Mountain varies from an excellent aphyric translucent brown glass to glass with large devitrified spherulites that make knapping impossible. This character of the fabric is probably why there is so much test knapping at the sources – a need to determine the quality of the nodules before transport. While spherulitic fabric occurs in all the Jemez Mountain obsidian, it seems to be most common in the Cerro Toledo glass and may explain why Valle Grande obsidian occurs in sites a considerable distance from the caldera even though it is not secondarily distributed outside the caldera while Cerro Toledo obsidian is common throughout the Rio Grande alluvium. Indeed, in Folsom period contexts in the Albuquerque basin, only Valle Grande obsidian was selected for tool production even though Cerro Toledo obsidian is available almost on-site in areas such as West Mesa (LeTourneau et al. 1996). So, while Cerro Toledo Rhyolite obsidian is and was numerically superior in the Rio Grande Basin, it wasn’t necessarily the preferred raw material.

Cerro Toledo Rhyolite (Cerro Toledo and Rabbit Mountain combined)

Elemental concentrations for Cerro Toledo Rhyolite obsidian source samples (all measurements in parts per million)

| SAMPLE | Ti | Mn | Fe | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba | Pb | Th |

| BCC-1 | 600 | 10616 | 217 | 5 | 66 | 192 | 97 | 44 | ||||

| BCC-3 | 552 | 9986 | 215 | 5 | 66 | 187 | 97 | 49 | ||||

| BCC-4 | 547 | 10102 | 214 | 5 | 62 | 183 | 99 | 42 | ||||

| OR-1 | 550 | 10278 | 222 | 0 | 66 | 192 | 103 | 43 | ||||

| OR-2 | 425 | 8727 | 190 | 4 | 59 | 175 | 94 | 42 | ||||

| OR-3 | 534 | 9921 | 216 | 6 | 65 | 188 | 97 | 42 | ||||

| OR-4 | 577 | 10218 | 218 | 5 | 69 | 188 | 99 | 42 | ||||

| OR1B | 536 | 9810 | 214 | 0 | 63 | 182 | 103 | |||||

| OR2B | 408 | 8242 | 179 | 1 | 58 | 162 | 92 | |||||

| CCA-1 | 499 | 9446 | 197 | 4 | 60 | 174 | 90 | 39 | ||||

| CCA-2 | 516 | 9714 | 211 | 6 | 66 | 189 | 98 | 0 | ||||

| CCA-3 | 529 | 9759 | 208 | 0 | 60 | 184 | 97 | 41 | ||||

| 081199-1-1 | 199 | 7 | 62 | 178 | 96 | 0 | ||||||

| 081199-1-2 | 198 | 7 | 61 | 177 | 94 | 1 | ||||||

| 081199-1-3 | 200 | 7 | 62 | 179 | 96 | 1 | ||||||

| 081199-1-4 | 207 | 6 | 63 | 187 | 99 | 1 | ||||||

| 081199-1-5 | 204 | 6 | 63 | 181 | 98 | 4 | ||||||

| 081199-1-6 | 204 | 7 | 63 | 184 | 99 | 9 | ||||||

| 081199-1-7 | 205 | 6 | 63 | 182 | 99 | 0 | ||||||

| 081199-1-8 | 217 | 7 | 67 | 193 | 105 | 15 | ||||||

| 080900-1 | 205 | 8 | 63 | 177 | 100 | 19 | ||||||

| 080900-2 | 204 | 7 | 62 | 175 | 99 | 3 | ||||||

| 080900-3 | 201 | 7 | 62 | 172 | 97 | 3 | ||||||

| 080900-A1 | 203 | 8 | 62 | 177 | 99 | 73 | ||||||

| 080900-A2 | 204 | 7 | 63 | 175 | 99 | 14 | ||||||

| 080900-A4 | 203 | 6 | 63 | 176 | 98 | 0 | ||||||

| 080900-A5 | 209 | 6 | 65 | 184 | 103 | 5 | ||||||

| 080900-A6 | 210 | 7 | 62 | 171 | 97 | 1 | ||||||

| 080899-3-1 | 897 | 584 | 11589 | 112 | 222 | 9 | 65 | 179 | 100 | 0 | 41 | 21 |

| -2 | 1138 | 545 | 12001 | 119 | 285 | 9 | 64 | 196 | 105 | 4 | 43 | 30 |

| -3 | 862 | 441 | 9859 | 84 | 187 | 9 | 60 | 167 | 100 | 0 | 28 | 23 |

| -4 | 932 | 553 | 11002 | 104 | 215 | 14 | 68 | 186 | 102 | 0 | 40 | 35 |

| -5 | 819 | 452 | 9918 | 95 | 194 | 11 | 59 | 171 | 98 | 0 | 35 | 31 |

| -6 | 980 | 527 | 11250 | 103 | 215 | 9 | 65 | 184 | 101 | 0 | 38 | 29 |

| -7 | 867 | 510 | 10595 | 97 | 210 | 10 | 66 | 175 | 97 | 0 | 36 | 25 |

| -8 | 881 | 463 | 10365 | 100 | 204 | 9 | 63 | 178 | 100 | 0 | 37 | 21 |

| -9 | 1094 | 504 | 10959 | 96 | 204 | 11 | 59 | 185 | 94 | 0 | 33 | 27 |

| -10 | 864 | 425 | 9686 | 82 | 187 | 9 | 62 | 167 | 100 | 0 | 31 | 29 |

| -11 | 837 | 460 | 9683 | 83 | 193 | 9 | 57 | 169 | 91 | 0 | 32 | 30 |

| -12 | 1011 | 427 | 10079 | 87 | 194 | 12 | 57 | 174 | 89 | 0 | 28 | 21 |

| -13 | 785 | 440 | 9849 | 96 | 195 | 11 | 60 | 181 | 94 | 0 | 27 | 19 |

| -14 | 1094 | 505 | 11851 | 103 | 221 | 11 | 65 | 183 | 105 | 0 | 43 | 27 |

| -15 | 887 | 419 | 9789 | 78 | 178 | 10 | 56 | 169 | 89 | 1 | 29 | 16 |

| -16 | 971 | 471 | 10634 | 99 | 205 | 9 | 62 | 172 | 96 | 0 | 31 | 22 |

| -17 | 1007 | 418 | 10058 | 88 | 183 | 9 | 63 | 170 | 93 | 0 | 32 | 26 |

| -18 | 913 | 448 | 10221 | 97 | 199 | 10 | 63 | 171 | 94 | 0 | 32 | 19 |

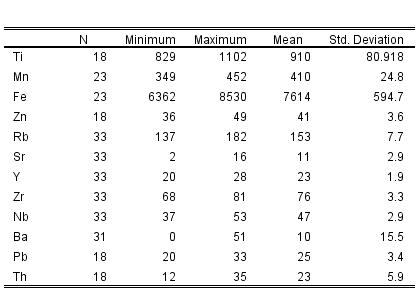

Mean and central tendency for data in table above

Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio)

Originally the primary domes like Cerro del Medio of Valles Rhyolite were not visited due to restrictions on entry to the caldera floor, surveys of the major stream systems radiating out from the caldera were examined for secondary deposits; San Antonio Creek and the East Jemez River, as well as the canyons eroding the outer edge of the caldera rim. After the land transfer to the Department of Agriculture and then Department of the Interior, samples were collected directly from Cerro del Medio proper.

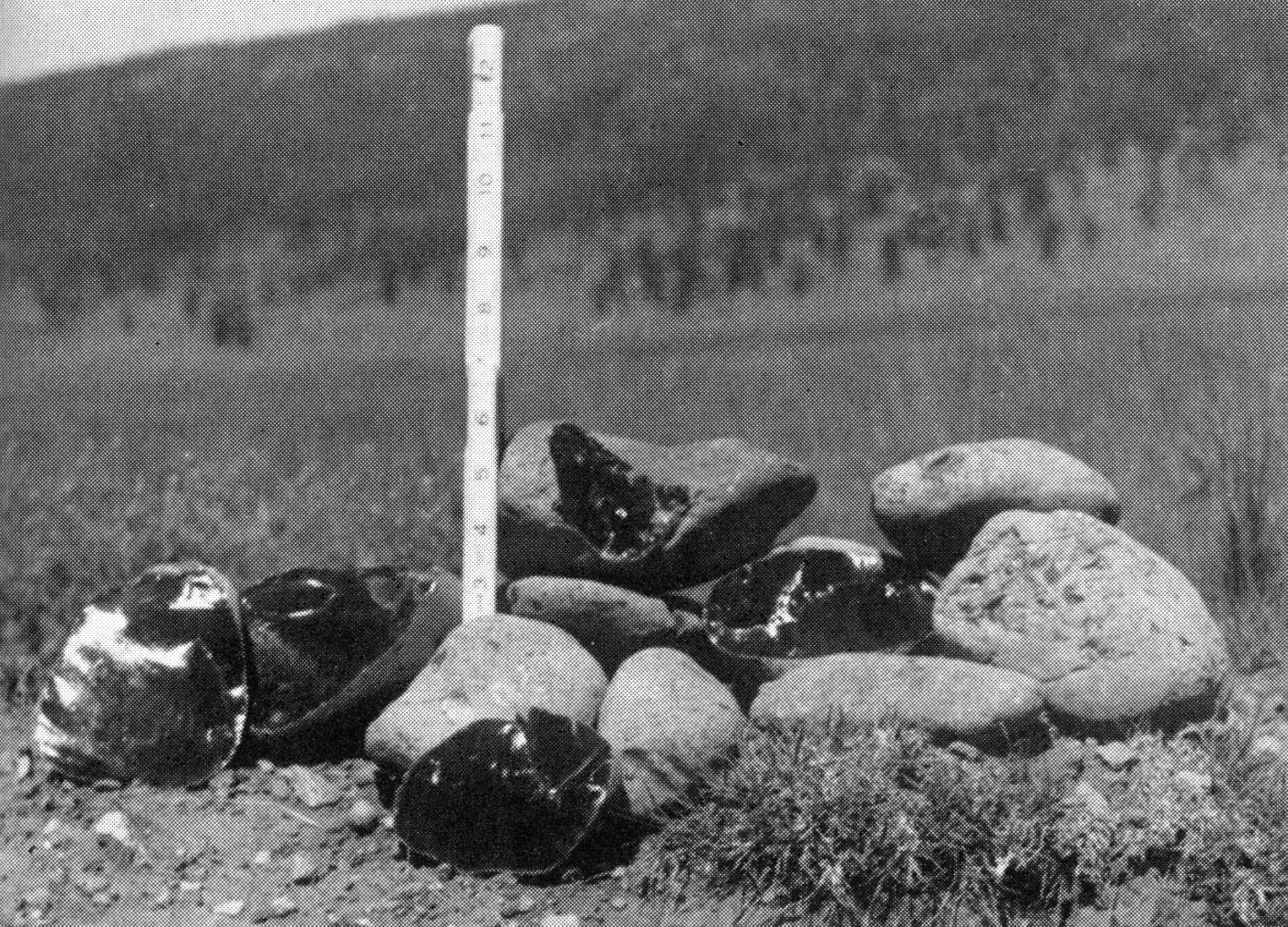

In 1956 two geology graduate students from the University of New Mexico published the first paper on archaeological obsidian in the American Southwest, a refractive index analysis (Boyer and Robinson 1956). In this examination of the Jemez Mountain sources, they noted that obsidian did not occur in the alluvium of San Antonio Creek where it crosses New Mexico State Highway 126, but did occur "in pieces as large as hen’s eggs, but the material is not plentiful and must be searched for with care" in the East Jemez River alluvium where it crosses State Highway 4 (Boyer and Robinson 1956:336). A return to the latter locality (Locality 102799-2) exhibited about the same scenario as that recorded 43 years earlier. The alluvium exhibits nodules up to 40 mm in diameter at a density up to 5/m2, but generally much lower. Boyer and Robinson did find nodules up to 15.5 cm in diameter along the upper reaches of San Antonio Creek as shown in their plate reproduced here (Boyer and Robinson 1956:337; Figure below).

Valles Rhyolite obsidian nodules photographed by Boyer and Robinson collected along San Antonio Creek in the caldera (1956:337).

My survey along San Antonio Creek from its junction with State Highway 126 for two miles upstream did not reveal any obsidian, as in the Boyer and Robinson study. It appears then that Valles Rhyolite obsidian does not enter secondary contexts outside the caldera, at least in nodules of any size compared to Cerro Toledo Rhyolite (see Church 2000; Shackley 2012).

Valles Rhyolite obsidian exhibits a fabric that seems to be a combination of El Rechuelos and Cerro Toledo. Some of the glass has that granular texture of El Rechuelos and some has devitrified spherulites similar to Cerro Toledo, and much of it is aphric black glass. Flakes of Valle Grande obsidian can be indistinguishable from El Rechuelos or Cerro Toledo in hand sample. An elemental analysis of samples collected by Dan Wolfman from Cerro del Medio and the nodules in San Antonio Creek in this study are identical. On the west slope of Cerro del Medio is an outcrop of artifact quality mahogany colored obsidian. The elemental composition is the same as the dominant black variety. It does appear in archaeological contexts, including in Archaic contexts in the El Segundo Archaeological Project sites to the southwest.

Elemental concentrations for Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio) obsidian source samples (all measurements in parts per million).

| Sample | Source Name | Location | Zone | Easting | Northing | Ti | Mn | Fe | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba |

| 102799-2-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 155 | 10 | 43 | 168 | 54 | 30 | |||

| 102799-2-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 157 | 10 | 44 | 172 | 55 | 25 | |||

| 102799-2-3 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 159 | 10 | 44 | 169 | 55 | 35 | |||

| 102799-2-4 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 158 | 10 | 43 | 171 | 55 | 27 | |||

| 102799-2-5 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 160 | 9 | 43 | 170 | 54 | 41 | |||

| 102799-2-6 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 154 | 10 | 42 | 167 | 54 | 39 | |||

| 102799-2-7 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 159 | 9 | 43 | 174 | 54 | 47 | |||

| 102799-2-8 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 162 | 10 | 44 | 168 | 55 | 41 | |||

| 102799-2-9 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 158 | 10 | 43 | 170 | 55 | 45 | |||

| 102799-2-10 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 166 | 10 | 43 | 168 | 54 | 23 | |||

| 102799-2-11 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 176 | 10 | 43 | 168 | 55 | 29 | |||

| 102799-2-12 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 140 | 11 | 40 | 178 | 53 | 26 | |||

| 102799-2-13 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 154 | 11 | 42 | 164 | 54 | 42 | |||

| 102799-2-14 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 144 | 10 | 41 | 179 | 55 | 25 | |||

| 102799-2-15 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 172 | 10 | 44 | 177 | 55 | 23 | |||

| 060304-1-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 884 | 430 | 8374 | 153 | 9 | 46 | 164 | 58 | |

| 060304-2-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 907 | 410 | 8449 | 150 | 12 | 32 | 162 | 49 | |

| 0304-2-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 979 | 444 | 9165 | 159 | 7 | 41 | 164 | 64 | 16 |

| 0304-2-3 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 934 | 406 | 8438 | 154 | 13 | 39 | 170 | 51 | 20 |

| 060304-2-4 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 961 | 456 | 9494 | 164 | 10 | 47 | 172 | 50 | 21 |

| 060304-3-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 1040 | 503 | 10031 | 171 | 10 | 46 | 177 | 57 | 17 |

| 060404-2-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 913 | 445 | 8551 | 147 | 5 | 37 | 177 | 53 | 16 |

| -2-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 954 | 462 | 8690 | 155 | 6 | 45 | 167 | 55 | 20 |

| -2-3 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 884 | 472 | 9096 | 163 | 8 | 40 | 170 | 48 | 15 |

| -2-4 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 1066 | 439 | 8604 | 151 | 13 | 49 | 171 | 63 | 11 |

| -2-5 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 892 | 403 | 8424 | 143 | 6 | 37 | 159 | 54 | 17 |

| 060404-4-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 838 | 447 | 8638 | 156 | 10 | 39 | 168 | 44 | 10 |

| -4-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 883 | 447 | 8575 | 150 | 13 | 43 | 168 | 56 | 44 |

| -4-3 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 938 | 439 | 8522 | 164 | 15 | 43 | 166 | 56 | 49 |

| -4-4 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 942 | 398 | 8505 | 148 | 8 | 43 | 153 | 48 | 42 |

| -4-5 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 13 | 369144 | 3975314 | 916 | 393 | 8358 | 143 | 14 | 37 | 151 | 54 | 43 |

| CDMA-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 593 | 13500 | 160 | 10 | 44 | 173 | 56 | 31 | ||||

| CDM3B | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 595 | 13549 | 159 | 10 | 44 | 174 | 56 | 39 | ||||

| CDMV-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 580 | 13319 | 158 | 10 | 44 | 173 | 55 | 32 | ||||

| CDMA-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 596 | 13536 | 158 | 10 | 43 | 174 | 55 | 34 | ||||

| CDMA-3-B | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 576 | 13220 | 156 | 10 | 43 | 172 | 54 | 35 | ||||

| CDM 3-1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 561 | 13465 | 178 | 10 | 42 | 170 | 54 | 62 | ||||

| CDM 3-2 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 579 | 13443 | 158 | 10 | 44 | 174 | 55 | 38 | ||||

| CDM 3-3 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 575 | 13243 | 156 | 10 | 43 | 171 | 54 | 27 | ||||

| CDM 1A | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 581 | 13325 | 156 | 10 | 43 | 172 | 54 | 31 | ||||

| CDM CM1 | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 585 | 13384 | 159 | 10 | 44 | 174 | 56 | 28 | ||||

| CDM CM-3-E | Valles Rhy-Cerro del Medio | Jemez Mtns, N NM | 606 | 14160 | 161 | 11 | 43 | 172 | 54 | 55 |

"CDM" samples were collected by Dan Wolfman, but the exact locality on Cerro del Medio is unknown.

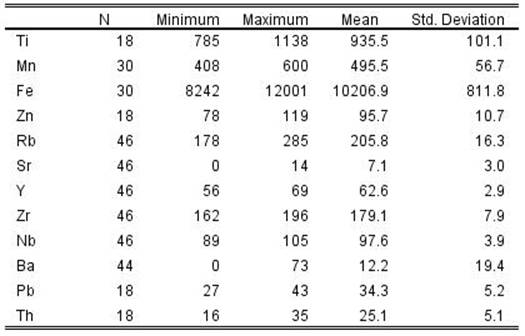

Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio) from table above

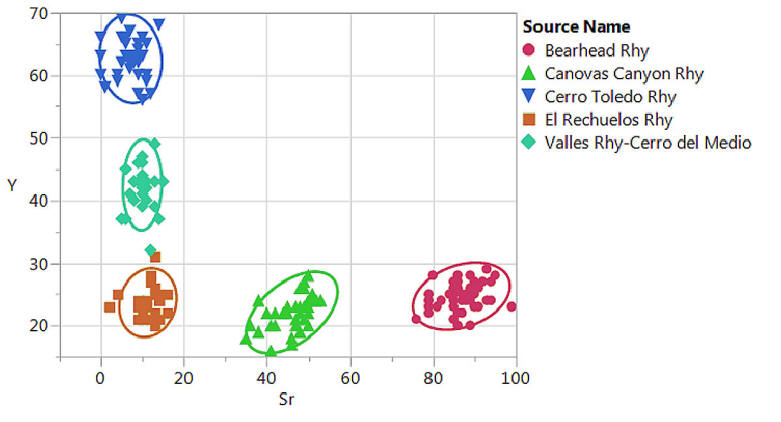

Canovas Canyon Rhyolite and Bear Springs Peak

Perlitic lava with remnant marekanites in the Canovas Canyon Rhyolite formation. Large marekanite in the center of image is 47 mm in diameter.

The oldest (Tertiary, ca. 8.8-9.8 mya) artifact quality obsidian source in the Jemez Mountains is the Bear Springs Peak dome complex, part of the Canovas Canyon Rhyolite domes and shallow intrusions (Tcc) as reported by Smith et al. (1970), and more recently by (Kempter et. al. 2004; see also Gardner 1985; Figure 3 here). These pre-caldera domes appear to be overlain by a rhyolite tuff, but field inspection suggests to Kempter et al. (2004) that they are contemporaneous. Our work at Bear Springs Peak and domes structures to the north suggest that the obsidian was produced from obsidian zones on the margins of the domes as part of a lava eruptive event. The lava has mostly devitrified into perlite, leaving the most vitreous portions of the flow as remnant marekanites (see image above).

Located at the far southern end of the Jemez Mountains, just south and adjacent to Jemez Pueblo (Walatowa) Nation land, this Tertiary Period source exhibits only relatively small marekanites now, most smaller than 2 cm in diameter (image above). Although the nodule size was apparently small, Bear Springs Peak obsidian was used in prehistory as a toolstone, and was recovered in samples analyzed from early historic period contexts at Zuni Pueblo, probably a result of relationships between the Zuni and Jemez in the 17th Century (see Howell and Shackley 2003; Shackley 2005:102-105). The source data suggest that this may be the “Bland Canyon & Apache Tears” source as reported by Glascock et al. (1999:863), collected by Wolfman and reported by him in 1994, and reported as “Canovas Canyon” by Church in his 2000 study of secondary deposits in the lower Rio Grande (Tables here).

As with many of the Tertiary Period sources in the Southwest, Bear Springs Peak obsidian is present as marekanites in perlitic lava at the Bear Springs Peak dome proper and domes trending along north-south faults active during the Mid-Miocene toward and into Jemez Pueblo land. Biotite in the crystalline rhyolite that underlies the obsidian zone yielded 40Ar/39Ar dates of 8.81±0.16 and 9.75±0.08 mya (Kempter et al. 2004).

Nodules up to 5 cm occur as remnants in the perlite not unlike the environment at Sand Tanks, Superior (Picketpost Mountain), Devil Peak, and many other Tertiary period sources in western North America (Shackley 2005; Shackley and Tucker 2001). The density of the nodules from pea gravel to 5 cm in the perlite lava is as high as 100/m2, although most of the marekanites are under 2 cm (see image above). The glass itself is nearly transparent in thin flakes similar to Cow Canyon and Superior obsidian, and some have noticeable dark black and nearly clear banding. It is an excellent media for tool production so that bipolar flakes are easily produced and pressure flaking is effective, typical of these high silica rhyolite glasses.

The marekanites have eroded into the stream systems to the south as far as the lower Rio Grande (Church 2000). Church recovered two specimens called “Canovas Canyon” in the Vado (Camp Rice) collection area in the Rio Grande gravels, south of Las Cruces; these two samples match the Bear Springs Peak data as presented here (Church 2000:660, Table IV). This suggests that the Canovas Canyon Rhyolite obsidian has eroded into the ancestral Rio Grande between about 9 million years ago and the present, although based on Church’s (2004) study are available today in very low proportions compared to Cerro Toledo Rhyolite, El Rechuelos, and Mount Taylor obsidian. Probably the reason this source is not found in archaeological contexts more frequently is that it simply cannot “compete” with the more recent large nodule, high quality sources just to the north including Cerro Toldedo Rhyolite, Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio) and El Rechuelos obsidian (Shackley 2005). However, the high quality, and perhaps its location on Jemez Pueblo territory, may have caused it to be viable as a toolstone, at least in the historic period, perhaps at a time when the Jemez and Zuni enjoyed an exchange relationship. The Zuni could have made trips into the Jemez Mountains for any number of reasons as a result of this relationship.

Elemental concentrations for Canovas Canyon Rhyolite obsidian source samples (all measurements in parts per million)

| Sample | Ti | Mn | Fe | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba | Pb | Th |

| 060604-1-1 | 849 | 431 | 5464 | 22 | 106 | 35 | 18 | 88 | 64 | 31 | ||

| -3 | 974 | 511 | 6447 | 23 | 117 | 41 | 16 | 104 | 60 | 38 | ||

| -4 | 1012 | 485 | 6443 | 31 | 113 | 41 | 20 | 100 | 58 | 29 | ||

| -5 | 976 | 497 | 6457 | 27 | 117 | 40 | 22 | 104 | 57 | 22 | ||

| -6 | 1087 | 609 | 7685 | 33 | 128 | 47 | 23 | 112 | 61 | 39 | ||

| -3 | 1029 | 530 | 6608 | 29 | 114 | 47 | 20 | 106 | 59 | 35 | ||

| -4 | 976 | 498 | 6245 | 32 | 113 | 48 | 19 | 107 | 48 | 31 | ||

| -5 | 1065 | 559 | 6710 | 29 | 118 | 50 | 22 | 108 | 53 | 30 | ||

| -6 | 990 | 516 | 6361 | 31 | 114 | 48 | 22 | 100 | 49 | 20 | ||

| -7 | 1067 | 510 | 6386 | 33 | 110 | 44 | 22 | 108 | 50 | 12 | ||

| -8 | 1259 | 451 | 9346 | 46 | 118 | 51 | 24 | 109 | 49 | 426 | 22 | 21 |

| -9 | 1172 | 393 | 8799 | 39 | 116 | 48 | 26 | 106 | 50 | 476 | 23 | 23 |

| -10 | 1157 | 422 | 8897 | 37 | 115 | 46 | 17 | 111 | 52 | 471 | 21 | 29 |

| -11 | 999 | 392 | 8313 | 38 | 110 | 49 | 23 | 114 | 53 | 462 | 23 | 33 |

| -12 | 1048 | 380 | 8162 | 76 | 106 | 36 | 20 | 96 | 51 | 414 | 24 | 34 |

| -13 | 1182 | 416 | 8782 | 43 | 122 | 51 | 25 | 111 | 47 | 454 | 27 | 29 |

| -14 | 1110 | 420 | 8773 | 39 | 123 | 49 | 26 | 115 | 55 | 481 | 25 | 33 |

| -15 | 1023 | 373 | 8204 | 37 | 111 | 47 | 21 | 105 | 55 | 448 | 33 | 30 |

| -16 | 1076 | 414 | 8569 | 41 | 119 | 48 | 23 | 115 | 55 | 464 | 25 | 18 |

| -17 | 1121 | 409 | 8456 | 56 | 117 | 50 | 23 | 108 | 48 | 447 | 28 | 27 |

| -18 | 987 | 371 | 7883 | 29 | 104 | 42 | 22 | 110 | 54 | 499 | 23 | 37 |

| -19 | 1248 | 402 | 8891 | 213 | 112 | 48 | 22 | 111 | 54 | 509 | 25 | 25 |

| -20 | 1059 | 451 | 8880 | 53 | 122 | 42 | 20 | 103 | 56 | 402 | 25 | 25 |

| -21 | 1020 | 455 | 8689 | 33 | 126 | 52 | 24 | 112 | 53 | 487 | 27 | 33 |

| -22 | 1207 | 447 | 9660 | 52 | 120 | 47 | 23 | 107 | 48 | 430 | 25 | 21 |

| -23 | 1109 | 425 | 8470 | 43 | 110 | 38 | 24 | 103 | 55 | 437 | 27 | 22 |

| -24 | 1257 | 398 | 9401 | 39 | 114 | 46 | 18 | 110 | 55 | 449 | 26 | 22 |

| -25 | 1053 | 423 | 8651 | 49 | 121 | 45 | 23 | 106 | 46 | 429 | 20 | 28 |

| -26 | 1028 | 400 | 8290 | 43 | 115 | 45 | 22 | 113 | 52 | 460 | 24 | 28 |

| -27 | 1114 | 426 | 8529 | 43 | 118 | 49 | 27 | 113 | 52 | 473 | 30 | 28 |

| -28 | 1032 | 426 | 8352 | 38 | 108 | 45 | 23 | 105 | 49 | 426 | 20 | 26 |

| -29 | 1133 | 411 | 9101 | 41 | 117 | 50 | 24 | 110 | 52 | 455 | 26 | 23 |

| -30 | 1381 | 371 | 9140 | 40 | 103 | 38 | 19 | 93 | 43 | 390 | 19 | 29 |

| -31 | 1054 | 374 | 8360 | 39 | 110 | 44 | 22 | 109 | 50 | 471 | 21 | 29 |

| -32 | 1131 | 450 | 9100 | 51 | 116 | 50 | 28 | 113 | 50 | 466 | 35 | 23 |

| -33 | 1143 | 402 | 9011 | 50 | 113 | 53 | 24 | 108 | 57 | 449 | 21 | 28 |

| -34 | 1111 | 385 | 8549 | 41 | 114 | 49 | 21 | 114 | 51 | 487 | 21 | 16 |

| -35 | 1188 | 374 | 8566 | 44 | 113 | 50 | 20 | 104 | 45 | 451 | 23 | 23 |

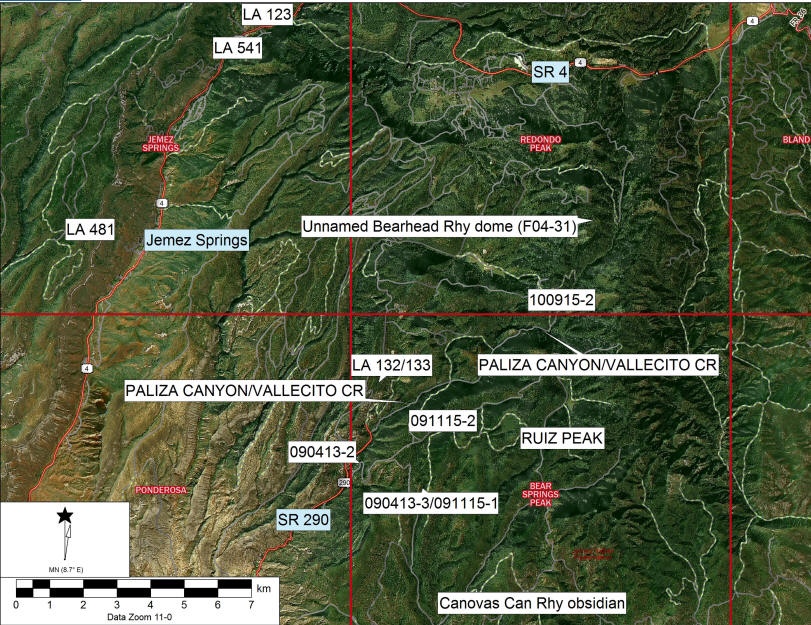

Mean and central tendency table for Canovas Canyon Rhyolite data from table above

Bearhead Rhyolite (Paliza Canyon)

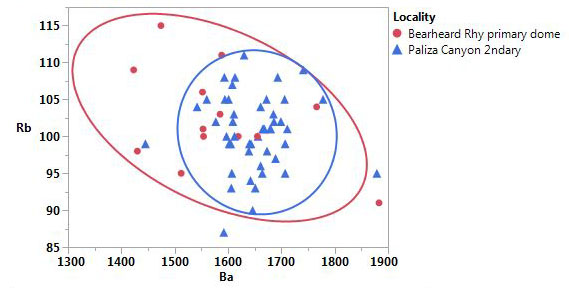

Recent geological and archaeological investigations published in New Mexico Geology of what has been called "Paliza Canyon" obsidian in the literature has been determined to be Bearhead Rhyolite, part of the Keres Group in the southern Jemez Mountains (Baugh and Nelson 1987; Shackley et al. 2016). The New Mexico Geology paper can be found here. The text, tables and figures are from that publication with some updates discussed below. The geological origin of all other archaeological obsidian sources in the Jemez Mountains have been reported and are well documented in the literature. But the so-called "Paliza Canyon" source, important as a toolstone to Pueblo Revolt Colonial period occupants of the Jemez Mountains area and present in regional archaeological contexts throughout prehistory, had remained unlocated and undocumented. The Bearhead Rhyolite origin for the "Paliza Canyon" obsidian (which we suggest should now be named “Bearhead Rhyolite”) solves this ambiguity and provides more precise geological and geographical data for archaeological obsidian source provenance in the region.

Update 8/24/21: On this date the F04-31 primary dome was visited and samples from that primary source were collected (the S082421-1-n samples in Table 3). As can be seen in the bivariate plots of four significant elements that there is little statistical difference between the obsidian from the primary dome and the secondary deposits just below in Paliza Canyon (see Figures 1 and 3). A 40Ar/39Ar date obtained by Goff yielded a date of 7.62 ± 0.44 Ma (Goff et al. 2006). As noted, this source has been eroding through ancestral Paliza Canyon (Vallecito Creek) into the ancestral Jemez River and on into the Rio Grande and seen as secondary deposits at least as far as Rio Grande Quaternary alluvium near Las Cruces, New Mexico, and presumably into Mexico (Church 2000; Shackley 2021). Further discussion is available in the New Mexico Geology paper here

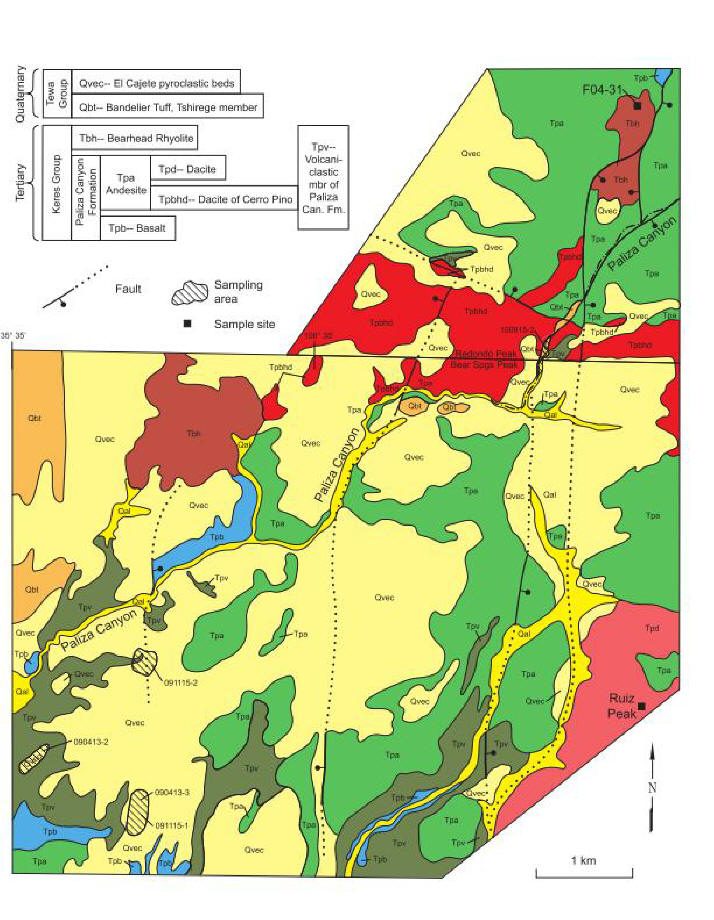

FIGURE 1---Orthophoto over digital elevation model of approximate location of collection localities (i.e. 090413-2 etc.), topographic points, USGS quadrangle borders in red, and Pueblo Revolt sites (LA numbers) from the 2009 and 2012 research that are present in our study area (Liebmann 2012; Shackley 2009a, 2012). Our precise collection localities are shown in Figure 2. Abbreviations: CR = creek; Rhy = rhyolite; SR = state highway; FR = Santa Fe National Forest route.

FIGURE 2---Simplified geologic map of the upper Paliza Canyon area, southern Jemez Mountains, New Mexico (modified from Kempter et al., 2004 and Goff et al., 2006 with labels and terminology from Goff et al., 2011). Qal (dark yellow) = stream alluvium; Qvec (pale yellow) = El Cajete Pyroclastic Beds; moderately sorted beds of rhyolitic pyroclastic fall and thin pyroclastic flow deposits (74.7±1.3 ka, Zimmerer et al., 2016); locally the beds are extremely thin; Qbt (orange) = Tshirege Member, Bandelier Tuff; rhyolitic ignimbrite (1.25±0.01 Ma, Phillips et al., 2007); Tpv (olive green) = volcaniclastic deposits, debris flows, hyper-concentrated flows, and stream deposits of the Paliza Canyon Formation; Tbh (brown) = Bearhead Rhyolite; domes and flows of aphyric to slightly porphyritic lava (dome in northern Bear Springs Peak Quadrangle is 6.66±0.06 Ma, Kempter et al., 2004; faulted dome in Redondo Peak Quadrangle is 7.62±0.44 to 7.83±0.26 Ma, Goff et al., 2006); Tpa (green) = Paliza Canyon Fm. andesite, undivided, lava flows containing plagioclase and pyroxene (8.78±0.14 to 9.44±0.21 Ma, Justet, 2003); Tpd (rose) = Paliza Canyon Fm. dacite, domes and flows of very porphyritic lava, near Ruiz Peak; Tpbhd (red) = Paliza Canyon Fm. porphyritic biotite-hornblende dacite, dome and flows (9.24±0.22 Ma, Justet, 2003); Tpb (blue) = Paliza Canyon Fm. basalt, lava flows most containing visible olivine (9.45±0.07 to 9.54±0.08 Ma, Goff et al., 2006 and Kempter et al., 2004).

TABLE 1---Mean and central tendency for Bearhead Rhyolite obsidian from data in Table 3. The ashy rhyolite sample not included (see Table 3)

| Element | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | 1 Std. Deviation |

| Zn | 72 | 29 | 145 | 57.5 | 21.6 |

| Rb | 72 | 87 | 115 | 101.0 | 5.5 |

| Sr | 72 | 75 | 99 | 87.4 | 5.1 |

| Y | 72 | 20 | 31 | 25.0 | 2.3 |

| Zr | 72 | 112 | 142 | 128.5 | 7.0 |

| Nb | 72 | 27 | 41 | 33.4 | 2.9 |

| Ba | 72 | 1388 | 1883 | 1638.0 | 91.2 |

| Pb | 72 | 15 | 25 | 19.7 | 2.4 |

| Th | 72 | 7 | 24 | 14.4 | 3.6 |

Table 2. Oxide values (%) for one sample of Bearhead Rhyolite from the primary dome and USGS RGM-1 rhyolite standard

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | K2O | MgO | MnO | Na2O | TiO2 | Σ |

| 082421-1-2 (primary dome) | 75.27 | 13.28 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 4.90 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 4.20 | 0.19 | 99.69 |

| RGM-1 (this study) | 75.68 | 12.48 | 1.3 | 1.81 | 4.55 |

<0.1 |

0.04 | 3.77 | 0.2 | 99.82 |

| RGM-1 USGS recommended | 73.4 | 13.7 | 1.15 | 1.86 | 4.3 | 0.28 | 0.036 | 4.07 | 0.27 | 99.06 |

Data not normalized to USGS recommended values.

Table 3. "Raw" data of selected elements for Paliza Canyon obsidian, one sample of Bearhead Rhyolite ashy lava, and USGS RGM-1 rhyolite standard, (all measurements in parts per million)

| Sample (collection date) | Locality | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba | Pb | Th | rock type |

| S082421-1-1 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 46 | 109 | 93 | 24 | 130 | 36 | 1423 | 17 | 24 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-2 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 37 | 98 | 88 | 24 | 132 | 36 | 1430 | 17 | 19 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-3 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 48 | 106 | 90 | 24 | 135 | 38 | 1552 | 23 | 14 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-4 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 43 | 100 | 89 | 31 | 127 | 31 | 1554 | 18 | 16 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-5 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 46 | 103 | 86 | 26 | 136 | 38 | 1585 | 25 | 16 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-6 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 50 | 101 | 85 | 27 | 139 | 33 | 1553 | 18 | 15 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-7 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 61 | 115 | 94 | 26 | 135 | 39 | 1474 | 24 | 15 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-8 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 48 | 111 | 95 | 29 | 136 | 33 | 1588 | 23 | 24 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-9 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 46 | 100 | 87 | 25 | 132 | 35 | 1619 | 21 | 23 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-10 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 41 | 95 | 85 | 26 | 136 | 35 | 1512 | 15 | 9 | obsidian |

| S082421-1-11 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 29 | 107 | 75 | 23 | 124 | 34 | 1388 | 21 | 11 | rhyolite (ashy) |

| F04-31 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 45 | 91 | 79 | 25 | 123 | 32 | 1883 | 15 | 18 | obsidian |

| F04-31 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 46 | 104 | 90 | 25 | 142 | 32 | 1766 | 22 | 16 | obsidian |

| F04-31 | Bearheard Rhy primary dome | 44 | 100 | 85 | 27 | 132 | 29 | 1655 | 21 | 17 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 81 | 101 | 91 | 23 | 132 | 34 | 1667 | 19 | 13 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 117 | 103 | 89 | 26 | 121 | 33 | 1611 | 20 | 12 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 145 | 87 | 76 | 21 | 112 | 30 | 1592 | 16 | 14 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 124 | 107 | 90 | 23 | 120 | 32 | 1608 | 20 | 18 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 111 | 95 | 79 | 22 | 117 | 32 | 1664 | 18 | 21 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 92 | 99 | 87 | 22 | 126 | 38 | 1605 | 18 | 14 | obsidian |

| 090413-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 92 | 101 | 79 | 24 | 119 | 34 | 1711 | 19 | 13 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 56 | 109 | 94 | 24 | 128 | 34 | 1741 | 24 | 12 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 61 | 100 | 87 | 25 | 121 | 36 | 1612 | 17 | 17 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 58 | 101 | 86 | 22 | 120 | 34 | 1665 | 19 | 12 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 52 | 103 | 86 | 28 | 123 | 35 | 1685 | 19 | 16 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 78 | 105 | 87 | 24 | 122 | 32 | 1672 | 21 | 12 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 101 | 97 | 85 | 23 | 113 | 30 | 1689 | 18 | 13 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 57 | 95 | 85 | 25 | 124 | 38 | 1607 | 15 | 15 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 81 | 102 | 82 | 24 | 120 | 31 | 1577 | 22 | 10 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 87 | 95 | 81 | 23 | 115 | 27 | 1707 | 17 | 17 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 89 | 100 | 85 | 25 | 119 | 27 | 1656 | 22 | 16 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 71 | 93 | 79 | 22 | 128 | 33 | 1606 | 18 | 10 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 47 | 99 | 86 | 26 | 120 | 32 | 1640 | 23 | 11 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 46 | 99 | 86 | 22 | 136 | 33 | 1445 | 18 | 12 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 56 | 105 | 89 | 20 | 138 | 37 | 1706 | 22 | 19 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 47 | 101 | 86 | 20 | 125 | 34 | 1680 | 19 | 19 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 53 | 105 | 93 | 24 | 128 | 29 | 1560 | 22 | 7 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 55 | 102 | 89 | 24 | 134 | 29 | 1609 | 20 | 13 | obsidian |

| 090413-3 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 47 | 96 | 85 | 24 | 130 | 31 | 1661 | 22 | 17 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 45 | 93 | 85 | 26 | 140 | 41 | 1651 | 18 | 17 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 43 | 100 | 86 | 26 | 130 | 31 | 1597 | 19 | 8 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 56 | 111 | 91 | 26 | 135 | 34 | 1630 | 23 | 18 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 49 | 102 | 86 | 27 | 129 | 35 | 1699 | 19 | 20 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 59 | 98 | 86 | 27 | 132 | 33 | 1673 | 19 | 14 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 54 | 101 | 88 | 25 | 129 | 34 | 1668 | 20 | 13 | obsidian |

| 091115-1 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 54 | 105 | 89 | 28 | 137 | 36 | 1601 | 20 | 15 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 51 | 101 | 89 | 24 | 129 | 33 | 1679 | 19 | 11 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 49 | 99 | 88 | 25 | 125 | 31 | 1707 | 18 | 17 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 52 | 99 | 85 | 21 | 135 | 30 | 1602 | 22 | 20 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 41 | 104 | 85 | 26 | 130 | 29 | 1542 | 17 | 12 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 57 | 108 | 95 | 28 | 136 | 37 | 1613 | 25 | 12 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 55 | 105 | 90 | 26 | 128 | 32 | 1594 | 21 | 14 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 49 | 104 | 90 | 27 | 135 | 36 | 1661 | 21 | 14 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 50 | 95 | 84 | 25 | 127 | 35 | 1879 | 18 | 10 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 54 | 108 | 94 | 27 | 133 | 36 | 1693 | 19 | 11 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 42 | 94 | 80 | 28 | 121 | 31 | 1642 | 16 | 11 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 51 | 105 | 92 | 27 | 140 | 37 | 1778 | 20 | 14 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 45 | 98 | 88 | 24 | 122 | 32 | 1639 | 20 | 19 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 44 | 108 | 93 | 29 | 133 | 32 | 1593 | 21 | 13 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 44 | 99 | 99 | 23 | 128 | 34 | 1643 | 22 | 14 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 41 | 90 | 79 | 23 | 122 | 30 | 1646 | 16 | 11 | obsidian |

| 091115-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 50 | 102 | 94 | 27 | 132 | 31 | 1686 | 21 | 15 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 49 | 104 | 90 | 27 | 135 | 36 | 1661 | 21 | 14 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 50 | 95 | 84 | 25 | 127 | 35 | 1879 | 18 | 10 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 54 | 108 | 94 | 27 | 133 | 36 | 1693 | 19 | 11 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 42 | 94 | 80 | 28 | 121 | 31 | 1642 | 16 | 11 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 51 | 105 | 92 | 27 | 140 | 37 | 1778 | 20 | 14 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 45 | 98 | 88 | 24 | 122 | 32 | 1639 | 20 | 19 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 44 | 108 | 93 | 29 | 133 | 32 | 1593 | 21 | 13 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 44 | 99 | 99 | 23 | 128 | 34 | 1643 | 22 | 14 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 41 | 90 | 79 | 23 | 122 | 30 | 1646 | 16 | 11 | obsidian |

| 100915-2 | Paliza Canyon 2ndary | 50 | 102 | 94 | 27 | 132 | 31 | 1686 | 21 | 15 | obsidian |

| RGM1-S4 | 42 | 147 | 107 | 26 | 219 | 8 | 769 | 25 | 17 | ||

| RGM-1 (this study) | 39 | 151 | 104 | 27 | 218 | 8 | 806 | 24 | 18 | ||

| RGM-1 USGS recommended (mean) | 32 | 150 | 110 | 25 | 220 | 8.9 | 810 | 24 | 15 |

Figure 3. Ba/Rb and Zr/Sr bivariate plots of Bearhead Rhyolite dome F04-31 obsidian and secondary deposit obsidian below in Paliza Canyon from the data in Table 3. Confidence ellipses at 90%.

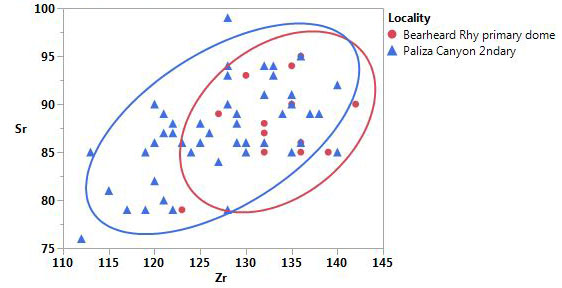

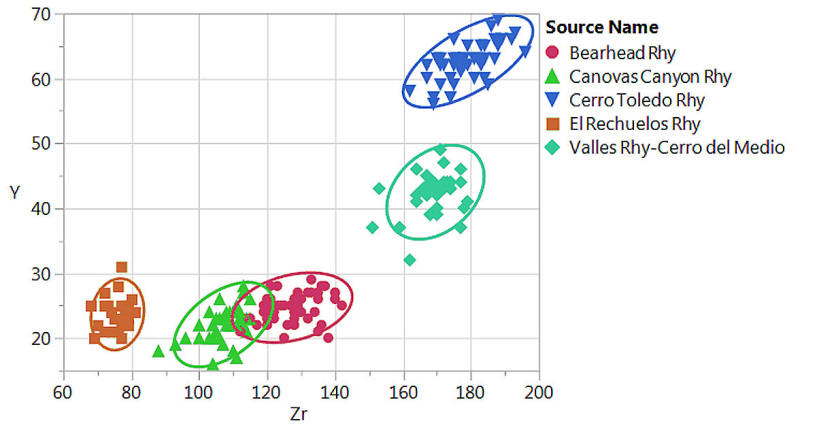

Discriminating Jemez Mountains sources with XRF data

The Jemez Lineament obsidian sources can be discriminated mainly with Y and Nb and one other incompatible element (i.e. Sr or Zr) as shown below. Niobium in the two Mount Taylor (Grants Ridge and Horace/La Jara Mesa) sources are quite distinctive with concentrations over 186 ppm, much higher than the Jemez Mountains sources (see Mt Taylor page here).

Sr versus Y and Zr versus Y bivariate plots of the Jemez Mountains obsidian sources discriminating all sources. Confidence ellipses at 95%.

References cited for Bearhead Rhyolite

Baugh, T.G., and Nelson, F.W. Jr. 1987, New Mexico obsidian sources and exchange on the Southern Plains: Journal of Field Archaeology, v.14, p. 313-329.

Church, T., 2000, Distribution and sources of obsidian in the Rio Grande gravels of New Mexico: Geoarchaeology, v. 15, p. 649-678.

Gardner, J.N., Goff, F., Garcia, S., and Hagan, R.C., 1986, Stratigraphic relations and lithologic variations in the Jemez Volcanic Field, New Mexico: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 91, B2, p. 1763-1778.

Gardner, J.N., Sandoval, M.M., Goff, F., Phillips, E., and Dickens, A., 2007, Geology of the Cerro Del Medio moat rhyolite center, Valles caldera, New Mexico, in Kues, B.S., Kelley, S.A., and Lueth, V.W., eds., Geology of the Jemez Region II: New Mexico Geological Society, 58th Annual Field Conference, Guidebook, p. 367-372.

Gardner, J.N., Goff, F., Kelley, S., and Jacobs, E., 2010, Rhyolites and associated deposits of the Valles-Toledo caldera complex: New Mexico Geology, v 32, p. 3-18.

Glascock, M.D., Kunselman, R. and Wolfman, D., 1999, Intrasource chemical differentiation of obsidian in the Jemez Mountains and Taos Plateau, New Mexico: Journal of Archaeological Science, v. 26, p. 861-868.

Goff, F., and Gardner, J.N., 2004, Late Cenozoic geochronology of volcanism and mineralization in the Jemez Mountains and Valles caldera, north central New Mexico, in Mack G. and Giles, K. eds., The Geology of New Mexico —A Geologic History: New Mexico Geological Society, Special Publication 11, p. 295-312.

Goff, F., Kues, B.S., Rogers, M.A., McFadden, L.D., and Gardner J.N. eds., 1996, The Jemez Mountains region: New Mexico Geological Society, 47th Annual Field Conference, Guidebook, 484 p.

Goff, F., Gardner, J.N., Reneau, S.L., and Goff, C.J., 2006, Geology of the Redondo Peak 7.5 minute quadrangle, Sandoval County, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Open-File Geologic Map OF-GM 111, scale 1:24,000.

Goff, F., Gardner, J.N., Reneau, S.L., Kelley, S.A., Kempter, K.A., and Lawrence, J.R., 2011, Geologic map of the Valles caldera, Jemez Mountains, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Geologic Map 79, scale 1:50,000.

Justet, L., 2003, Effects of basalt intrusion on the multi-phase evolution of the Jemez volcanic field, New Mexico [ Ph.D. thesis], Las Vegas, University of Nevada, 248 p.

Kempter, K., Osburn, G.R., Kelley, S.A., Rampey, M., Ferguson, and J.N. Gardner, J.N., 2004, Preliminary geologic map of the Bear Springs Peak quadrangle, Sandoval County, New Mexico: New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Open-File Geologic Map OF-GM 74, scale 1:24,000.

Liebmann, M., 2012, Revolt: An archaeological history of pueblo resistance and revitalization in the 17th century New Mexico: Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 328 p.

Phillips, E.H., Goff, F., Kyle, P.R., McIntosh, W.C., Dunbar, N.W., and Gardner, J.N., 2007, The 40Ar/39Ar age constraints on the duration of resurgence at the Valles caldera, New Mexico: Journal of Geophysical Research, v.112, B08201, 15 p.

Self, S., Goff, F., Gardner, J.N, Wright, J.V., and Kite, W.M., 1986, Explosive rhyolitic volcanism in the Jemez Mountains: vent locations, caldera development, and relation to regional structure: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 91, B2, p. 1779-1798.

Self, S., Kirchner, D.E., and Wolff, J.A., 1988, The El Cajete Series, Valles Caldera, New Mexico: Journal of Geophysical Research, v. 93, B6, p. 6113-6127.

Shackley, M.S., 2005, Obsidian: geology and archaeology in the North American Southwest: Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 264 p.

Shackley, M.S., 2009a, Source provenance of obsidian artifacts from six ancestral pueblo villages in and around the Jemez Valley, Northern New Mexico: unpublished report prepared for Matthew Liebmann, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, 17 p.

Shackley, M.S., 2009b, Two newly discovered sources of archaeological obsidian in the Southwest: archaeological and social implications: Kiva v. 74, p. 269-280.

Shackley, M.S., 2009c, The Topaz Basin archaeological obsidian source in the Transition Zone of central Arizona: Geoarchaeology, v. 24, p. 336-347.

Shackley, M.S., 2011, An introduction to X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis in archaeology, in Shackley, M.S., ed., X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (XRF) in Geoarchaeology: New York, Springer Publishing, p. 7-44.

Shackley, M.S., 2012, Source provenance of obsidian artifacts from Astialakwa (LA 1825) Jemez Valley, New Mexico: unpublished report prepared for Matthew Liebmann, Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, 11 p.

Shackley, M.S., 2021, Distribution and sources of archaeological obsidian in Rio Grande alluvium New Mexico, USA. Geoarchaeology 36:808-825.

Wolfman, D., 1994, Jemez Mountains chronology study: Santa Fe, Museum of New Mexico, Office of Archaeological Studies, 234 p.: http://members.peak.org/~obsidian/pdf/wolfman_1995.pdf (accessed September 2016).

Zimmerer, M.J., Lafferty, J., and Coble, M.A., 2016, The eruptive and magmatic history of the youngest pulse of volcanism at the Valles caldera: Implications for successfully dating late Quaternary eruptions: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, v. 310, p. 50-57.

![]() Back to SW Obsidian Sources page

Back to SW Obsidian Sources page

Revised: 28 October 2021